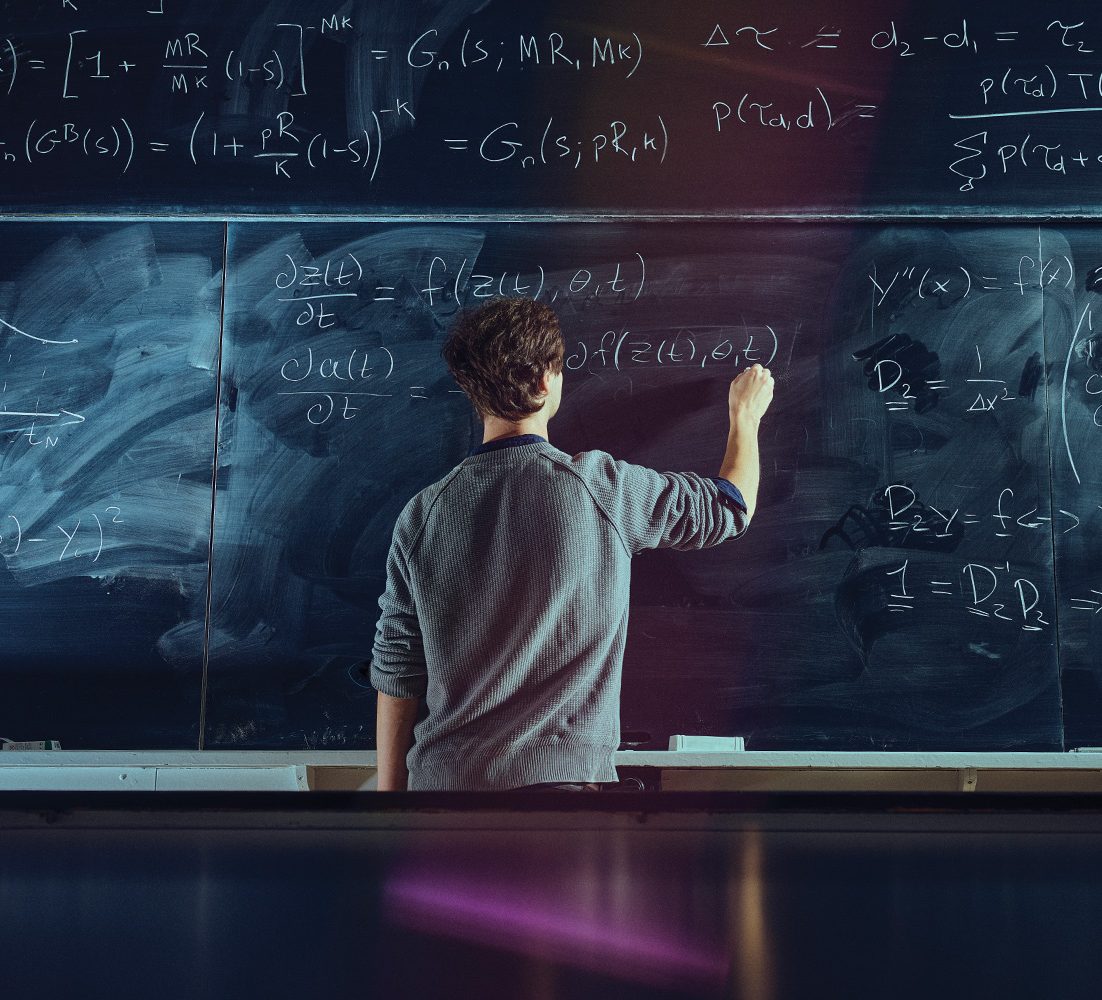

In her home in Aarhus, art historian Pernille Leth-Espensen has a drawing produced by a robotic arm. The drawing comes from the artwork MEART – the Semi-Living Artist, in which brain cells from a rat are cultured in a Petri dish with electrodes. Impulses from the cells are sent via the Internet to a robotic arm that makes the drawings thereafter. The brain cells are located in a laboratory in the United States, but the robotic arm has been exhibited around the world.

– The work of art explores our perception of what consciousness is and the relationship between consciousness and the body. It also explores the phenomenon that a living body is not always an entity in time and space any more. In this artwork, the brain is in one place and the body is somewhere else – if we consider the robotic arm to be a body, says Pernille Leth-Espensen, a postdoctoral fellow at Aarhus University.

In 2014, the Novo Nordisk Foundation awarded Pernille Leth-Espensen a Mads Øvlisen Postdoctoral Fellowship in art and bioscience and the natural sciences. Her project will focus on artists creating living artworks with cell and tissue culture technologies. She will investigate the ways in which the artists thematize how technological development affects our understanding of the body and our conception of identity and subjectivity. In connection with this, the project will also discuss the ethical and biopolitical implications to which the artworks turn our attention.

– Technology is developing extremely rapidly and has an enormous impact on our lives. As a result, we must also consider the broader philosophical and ethical implications. Works of art provide a good opportunity for doing this because artists use technology differently than researchers and focus on aspects that are not as well known to the public, says Pernille Leth-Espensen.

MEMORIES OF A BODY

One artwork Pernille Leth-Espensen will analyse is The Vision Splendid by Australian artist Alicia King. This artwork exhibits live cells from a 13-year-old girl – 40 years after her death. King purchased the cells online and has displayed them together with small handmade glass bones in a bioreactor that drips nutrient medium on the cells to keep them alive.

– The cell lines constitute a concrete material relic of a body, but the subjectivity has disappeared. Similar to a war memorial, the artist is creating a work as an artistic monument or celebration of a person whose body is being used for scientific research, says Pernille Leth- Espensen. She adds that cell culture methods today are standard procedure in laboratories throughout the world, and people may therefore have gradually lost the ability to wonder that cells from a human body can continue to live outside that body.

During the project, Pernille Leth-Espensen will also return to SymbioticA, an art school and research laboratory at the University of Western Australia where artists have opportunities to create artworks in the laboratory. On her last visit there, she cultured cells and genetically modified bacteria.

– This practical laboratory experience is important because it provides me with better opportunities to understand and interpret the works of art, she concludes.

Peter Nørgaard Larsen, Chair of the Committee on Art History Research – Mads Øvlisen Scholarships, says:

– The encounter with bioscience challenges and enriches research in art and the humanities. We need such projects as that of Pernille Leth-Espensen, which can elucidate how this interaction affects and possibly alters our individual understanding and perception of what art is and what it can do.